My Life Story

This page is a bit of an indulgence

I have decided to chronicle my life through words, photographs, and music as a way to document the experiences which have shaped me.

It’s a personal archive, with snippets gathered from an extraordinary life.

Of course my life is explored in a tongue in cheek fashion in my book “Dancing the Skies and Falling with Style”

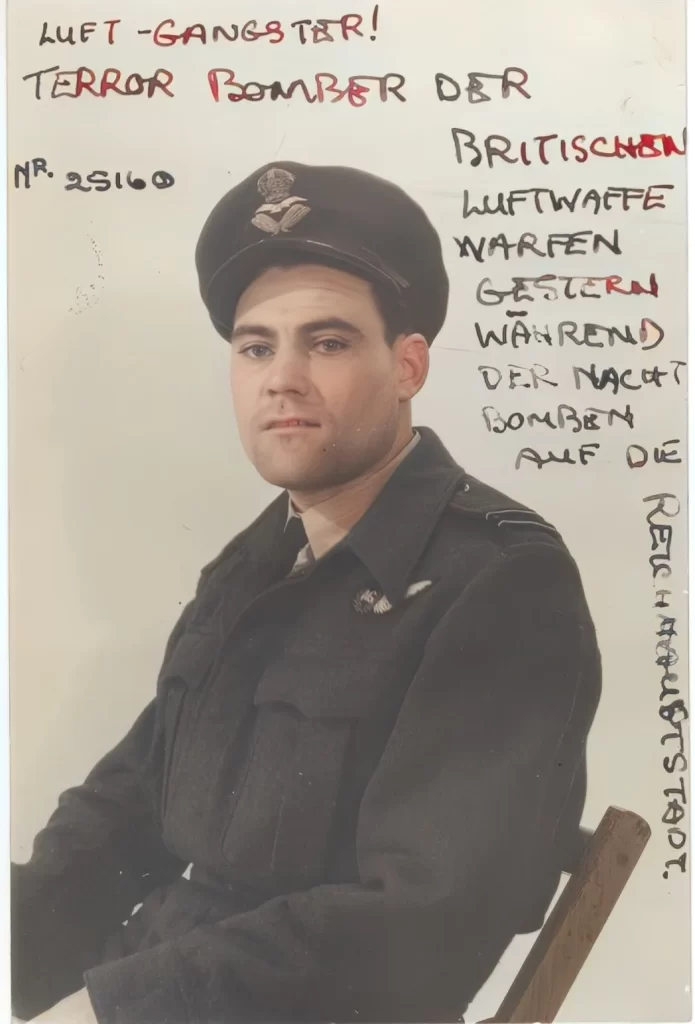

1st August 1942

I suppose my story starts before I was born

My father was in RAF Bomber Command during the Second World War, he survived being shot down on 1st August 1942 to spend the next three years as a Prisoner of War.

RAF Bomber Command aircrew in World War II faced some of the highest mortality rates of any Allied service. Of the 125,000 men who served, more than 55,000 were killed — a staggering 44% death rate. The odds of surviving a single 30-mission tour were slim, and many who completed one tour were sent back for a second.

My father was shot down approaching his 40th mission

The level of danger was compounded by night operations, flak, enemy fighters, mechanical failures, and the sheer length of missions — yet many men returned to duty repeatedly, knowing their chances.

Despite their extraordinary bravery and sacrifice, Bomber Command was later politically sidelined. In the postwar years, unease about the morality of area bombing — particularly the destruction of cities like Dresden — led to a deliberate effort to downplay their contribution. There was no specific campaign medal for Bomber Command, and they were notably excluded from the official victory celebrations in 1946. Their role, vital to the war’s outcome, was overshadowed by political expediency, and recognition came only decades later.

🎶 Summer 1942 Over Germany

Aden 1966

In 1965, my father was posted to Aden, Yemen.

The following year, aged sixteen, I visited during the school holidays — utterly unprepared for life beyond the confines of my all-boys public school. I spent much of my time at the local beach club, where I met a girl from Crater, a district considered off-limits due to terrorist activity and poor security.

I developed the kind of intense, naïve crush only a schoolboy can. Despite the risks, I accepted an invitation to visit her home — a grand, heavily guarded compound that felt more like a palace. A chaperone shadowed us everywhere, so the evening remained entirely innocent — which was probably just as well, since I wouldn’t have known what to do anyway.

Not long after, Crater was retaken by British forces. I heard that her house had been attacked and partly destroyed. Rumours circulated that her entire family had been killed.

I never saw her again.

🎶 My Scheherazade with the Desert Eyes

1968 College of Air Training

I joined the College of Air Training at Hamble in early 1968, after leaving school the previous year. The course was notoriously demanding, with a high failure rate and constant pressure. Ground school was intense—four months of complex subjects like aerodynamics, navigation, and meteorology—followed by flying training on the Chipmunk, Cherokee, and Baron. Life at Hamble was spartan and tightly regulated, but camaraderie developed quickly. We let off steam in the pubs and broke rules more than once, but somehow, we made it through. I passed by the merest margin in July 1969, the same day man landed on the moon.

Looking back, it was the toughest but most formative year of my life

Why Tangle Knees? Well, every great story needs an unlikely muse — and at the College of Air Training, she was a legend. Known affectionately (and irreverently) as Tangle Knees, she managed to be both glamorous and pigeon-toed — and totally unforgettable. Whatever it was, she earned her place in my songbook — and in Hamble folklore.

🎶 Tangle Knees

1971 Calcutta

I joined British Overseas Airways Corporation BOAC in august 1969 and joined the Vickers VC10 fleet as a Second Officer. The VC10 was a four engined intercontinental jet capable of carrying 188 passengers.

In the early 1970s, political instability was widespread, and it had a profound effect on me—both personally and professionally. As a young airline pilot flying to the far corners of what remained of the British Empire, I saw first-hand the violence and upheaval that marked the end of an era. Hijackings were becoming common, and bomb threats—sometimes real—were part of the operational backdrop, especially in the Middle East and Africa.

I flew into Lagos during the Biafran War, and into Entebbe before and during Uganda’s descent into chaos under Idi Amin. In Beirut, I watched the “Paris of the Middle East” collapse into sectarian violence and destruction. The PLO’s actions caused major disruption to flight schedules, and in Johannesburg, apartheid was plain to see—its injustice inescapable. I also saw the quiet, grinding tragedies of famine in Ethiopia and India.

In Calcutta, we stayed at the Grand Hotel which was an oasis of privilege set in a sea of poverty and deprivation. Just outside the gates, a starving little girl stood with swollen belly and imploring eyes, cupping her hands in silent appeal.

I have never forgotten her face.

So this song is for her, written in the cadence of Kipling, as a reflection on what I saw. In 1971, just 24 years after independence, India still bore the scars of empire—its poverty, privilege, and proud defiance laid bare.

Flying in those days wasn’t just about aircraft and schedules. It was about witnessing history unfold—sometimes from the cockpit, and sometimes just a few steps beyond it.

🎶 By the Gutters of the Grand Hotel

1972 Astro-Navigation

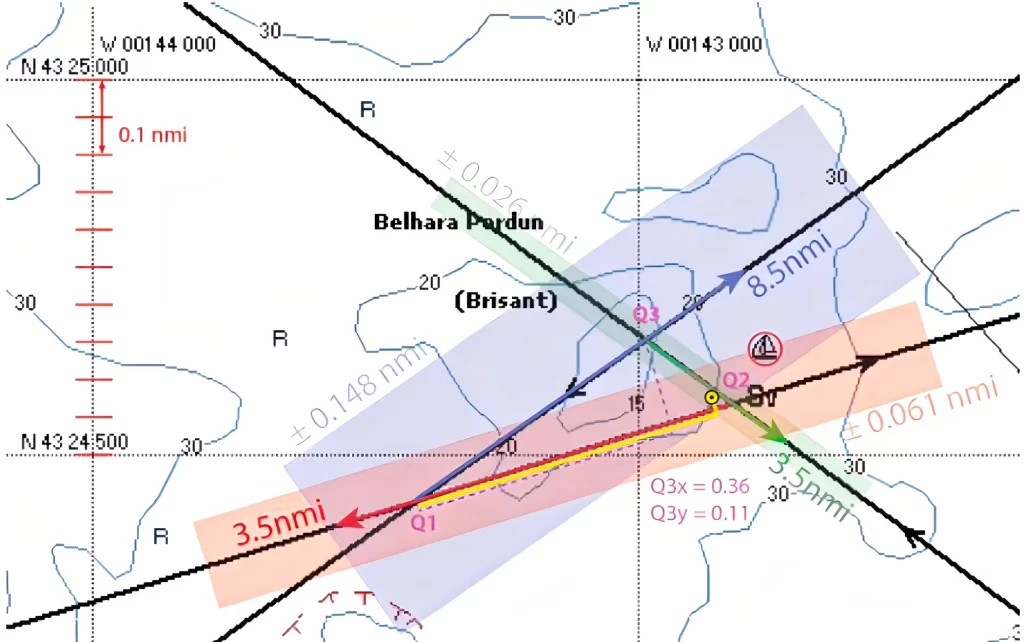

Before the advent of GPS and Inertial Navigation Systems (INS), long-range jet navigation relied on a combination of celestial, radio, and dead reckoning techniques, it was an art as much as a science.

Using a periscopic sextant mounted through the fuselage roof, the navigator measured the altitudes of three celestial bodies — typically stars, planets, or the Sun — to obtain a position fix. Each star shot took two minutes and could not be interrupted. The measured elevations were plotted as lines of position on a Mercator chart; the point where they ideally intersected indicated the aircraft’s location. In practice, the lines rarely met precisely, forming a triangle of uncertainty known as a ‘cocked hat.’

The accuracy of the fix depended on timekeeping, angle measurement, and atmospheric clarity. At best, three fixes per hour were possible, meaning positional certainty always lagged behind by several hundred miles. Supplementary aids such as LORAN and long-range HF radio beacons were employed when available, but over the oceans — particularly under cloud cover — celestial navigation remained the most reliable method. Navigation in jet aircraft was a continuous task, vulnerable to wind errors, with jet streams over the Pacific sometimes exceeding 300 knots. Even minor miscalculations could result in significant track deviations, underscoring the skill and vigilance required before satellite precision became the norm.

🎶 Tabasco da Gama the Red-Hot Navigator

1973 Iran

I visited Iran frequently during the early 1970’s during the reign of the Shah. I have skied at Shemshak, visited the Caspian Sea on a mule and dined on a table in the middle of a mountain stream drinking “1001” wine.

But it was the history and the culture which fascinated me particularly the 14th Century poet Hafez from Shiraz, Persia, who is a revered figure in Persian literature. Known for his profound knowledge of the Quran, his poetry blends Sufi mysticism with lyrical beauty, offering insights into love, spirituality, and the divine.

His ghazals capture the essence of Persian culture and have inspired countless artists and thinkers worldwide.

In tribute to Hafez, I’ve set his poem “All the Spheres” to music, hoping to share its timeless beauty and spiritual resonance. Hafez’s work serves as a bridge across cultures and time, uniting people through its universal themes.

🎶 Hafez—All the Hemispheres

1975 Hitching to St. Tropez.

In early 1975, my time on the VC10 came to an end. I was due to be posted to the sleek, brand-new Boeing 747 as a First Officer.

I’d enjoyed my apprenticeship on the “Iron Duck,” but it was time to broaden my horizons.

Unfortunately, delays in aircraft deliveries pushed back my start date by six months.

The message was blunt: don’t call us — we’ll call you.

So I did exactly that.

At 25, hopelessly in love with Brigitte Bardot, I set off to hitchhike to St Tropez in search of the girl of my dreams.

It didn’t go quite to plan. I ended up working as a plongeur in a dingy restaurant — and promptly fell for the owner’s wife, who just happened to look uncannily like the real BB.

So, in a way, I did find what I was looking for

In the middle of it all, the call finally came. I was summoned back to join the 747 fleet, and just like that, my Riviera dreams evaporated.

🎶 Hitchin’ to St. Tropez

1976 Where the waters meet

In early 1976, I moved into a split-level bachelor pad designed by my best mate — the kind of place where the bar wasn’t just central, it was architectural. We spent most of our time trying to outdo each other, whether it was charm, conquests, or beer consumption. That summer, England roasted in a record-breaking heatwave, and the garden by the river became the stage for a string of unruly parties.

There was willow root in the way by the river which refused to budge, no matter how many scaffold poles or heroic efforts we threw at it. Even the local River Police joined in — at first for the barbecues and banter, but eventually for a doomed operation involving their launch, a steel hawser, and far too much rum. The plan? Use brute force to pull the root free. The result? A flying transom, a stunned crowd, and a shattered launch drifting home in disgrace.

The next day, word came that the boat had slipped its moorings, sailed itself over the weir at Sunbury Lock, and smashed to pieces — poetic justice, perhaps, or just the natural end to a riverside epic.

We attempted a solemn pilgrimage to the wreck site in my lovingly restored dinghy, which had taken me two years to finish. It lasted all of ten minutes. Eight of us piled in, and the little clinker-built craft sank in the middle of the river like a stone. I’d always assumed wooden boats floated, but apparently not under that kind of weight. All that varnish, all that labour, all gone to the bottom.

The following year, my mate decided to get married. His fiancée was less than thrilled when I asked if I could stay on after the honeymoon.

🎶 The Ballad of the Stubborn Root

1977 End of an era

I moved out in 1976, just ahead of the wedding. I continued flying worldwide, building experience, but nothing quite prepared me for the mayhem of the stag weekend.

Jersey didn’t know what hit it when twenty pilots and rugby players descended on the Old Court Inn in St Aubin. I arrived late on Friday night to find the groom-to-be already soaked, drunk, and draped in seaweed after being launched into the harbour in a dinghy.

From there, the weekend spiralled spectacularly: beer-fuelled lunches turned to flying guitars, romantic prospects vanished mid-meal leaving us to foot a champagne-soaked bill, and our attempted arrest at the St Helier police station ended in us being told — in no uncertain terms — to piss off.

The final day saw our friend stained, literally, with dark oak varnish, then launched down an airport slope in a shopping trolley straight onto the apron between two parked aircraft.

The ferries were cancelled due to a seamen’s strike, but somehow, we blagged our way onto a Dan Air flight home — where we promptly relieved ourselves against the wheels on arrival, only to be met by a furious captain and a cloud of smoke. It had been, by all accounts, a fitting farewell to his bachelorhood.

🎶 No Life for a Single Man

1985 Falklands War

As a Senior First Officer, I flew one of the early 747 trooping flights into Mount Pleasant during the Falklands War. Although the fighting on the Islands had ceased, we were technically still at war with Argentina. The journey took us from Brize Norton to the volcanic outpost of Ascension, and then south into a bleak, wind-scoured landscape that looked more like the Yorkshire moors than a theatre of war.

The Captain and I spent our off-duty hours walking the battlefields — Longdon, Tumbledown, Sapper Hill — where brass shell cases, discarded boots, and rusting wire told stories more powerfully than any briefing. A wrecked Argentine Pucara lay nose-down in a peat bog, its wing draped over a barbed-wire minefield. It was hard not to think of Jorge Luis Borges’ bitter line: “A fight between two bald men over a comb.” A thousand men had died for sovereignty over a windswept archipelago few had heard of before 1982.

The air still felt charged with something unresolved — the futility of a war fought in a place so remote, so desolate, it barely seemed real.

And yet, for those who fought and those who flew there, it would remain unforgettable.

🎶 Falklands Lament

1989 North West Frontier

I was promoted to Captain in 1986 — the left-hand seat at last. With it came the final say, and the quiet thrill of knowing that every takeoff, every landing, every decision in the air now rested squarely on my shoulders. I relished the responsibility — and the view wasn’t bad either.

In 1989 I arranged a layover in Islamabad with the goal of finding my grandfather’s grave —who had served in the Royal Artillery, survived the whole of the First World War and died near the Khyber Pass in 1928 during one of the many Afghan Wars.

Armed only with a faded black-and-white photo of the headstone my brother and I set out during a five-day layover. A lightning strike shortly after take-off nearly cut short the trip, but once airborne, a discussion with a distinguished Pakistani passenger led to an unexpected offer: use of his personal car and driver. With the help of the hotel staff and our driver, we eventually arrived in Nowshera, where a retired bearer miraculously recognised the location in the photo.

Beneath a field of wild grass and red poppies, we uncovered the broken headstone of our grandfather, lying face down for decades. It was a profoundly emotional moment. A local stonemason — the grandson of the original stonemason agreed to restore it.

The next day, we hoped to travel to the Khyber Pass, but the region was restricted due to recent Russian incursions into Afghanistan. Access required official clearance. Through a stroke of luck and diplomacy — and with a small upgrade offered to the Chief of Police on our return flight — we were granted special passes. At Peshawar, we were provided with an armed escort and crossed into Afghanistan at Torkham, if only briefly. Later that day, we visited Darra, a remote frontier town famed for its handmade weapons.

As the visit concluded, I was presented with an exquisitely crafted pen-gun and a box of bullets by an elderly gunsmith as a gesture of gratitude. Though impressed, I ultimately decided the risk of carrying a concealed firearm through airport security outweighed its sentimental value. As our convoy disappeared into the desert dusk, I quietly threw the pen out of the window — leaving behind both the weapon and one of the most unforgettable experiences of my flying life.

🎶 The Twilight of the Raj

1990 beach Fleet

In 1990, I was faced with one of those career-defining choices.

Option one: stay at Heathrow, where the only thing flying high was industrial relations —a world of strikes, politics, and tension.

Option two: move to Concorde, where the air was rarefied and so were the egos. Everyone there seemed to be up their own backsides, and I’d never quite mastered the right handshake — all very “Wizard Prang, Old Boy!”.

Or there was option three: the Beach Fleet at Gatwick — a ragtag fleet of five ageing 747s dedicated to flying to the Caribbean.

The pay wasn’t great, but the lifestyle more than made up for it. Sand between your toes, steel drums drifting across the beach at sunset, and rum punch never far from reach — this was flying with a grin. The atmosphere was laid-back, the crews were tight-knit, and the sunshine never seemed to end.

On my very first flight to Trinidad, someone rather inconveniently jumped into one of my engines. I volunteered to clean it out, which says a lot about the spirit of the place — no drama, just get on with it and have a laugh afterwards.

I spent a few fantastic years there, and looking back, I wouldn’t have swapped it for all the champagne and Concorde kudos in the world.

🎶 We Only Fly to Party

2016 Greenland

In 2016, just a year after hanging up my wings for good, I found myself at a crossroads.

My career had ended—abruptly, cruelly—as the clock ticked one minute past my 65th birthday. One moment I was licensed to fly 550 people anywhere on Earth, the next I wasn’t allowed to fly commercially at all.

After nearly five decades in the air—first with British Airways, then seven remarkable years with Singapore Airlines, and finally with TNT out of Liège, I was unprepared for the vacuum which followed. I missed the adrenaline, the validation, the purpose.

So, at 66, I did the only sensible thing—I decided to ski across Greenland. It was a 600-kilometre, unsupported expedition, dragging an 85-kilo sledge across an icecap which rose to 10,000 feet. For five weeks, we slept in tents sometimes at -40°C, roped ourselves together to cross crevasses, scrambled down icefalls, and braced against savage snowstorms.

But the real menace was the Piteraq—a katabatic wind which can tear down from the icecap at over 300 kilometres per hour, flattening everything in its path. Each night, our survival depended on building two-metre-high walls of ice around our tents.

That wind, that place, that edge-of-the-world intensity—it brought back the rush I’d been missing.

This song is about the Piteraq.

🎶 I am the Piteraq

2021 Roobarb

This last section is purely sentimental. It’s not about storms or flying or perilous crossings — it’s a song for Roobarb, our utterly adorable Bouvier Bernois.

She’s a walking contradiction: noble yet daft, huge yet gentle, aloof yet somehow always underfoot. She has paws like frying pans, a coat like a shag carpet, and eyes that could melt granite.

Roobarb doesn’t bark — she simply is, and that’s quite enough.

This song is for her — because no adventure, no matter how extreme, quite compares to the quiet joy of a dog who thinks you’re the centre of the universe.

🎶 Roobarb

“Every new beginning comes from some other beginning’s end.”

Lucius Annaeus Seneca